A long time ago, I did some work for a client that had an out-of-date and inflexible billing system. The software would send invoices and monthly statements to the customers, who were then expected to remit payment to clear the balance on their account.

The business had recently introduced a new direct debit system. Customers who had signed a direct debit mandate no longer needed to send payments.

But faced with the challenge of introducing this change into an old and inflexible software system, the accounts department came up with an ingenious and elaborate workaround. The address on the customer record was changed to the address of the internal accounts department. The computer system would print and mail the statement, but instead of going straight to the customer it arrived back at the accounts department. The accounts clerk used a rubber stamp PAID BY DIRECT DEBIT, and would then mail the statement to the real customer address, which was stored in the Notes field on the customer record.

Although this may be an extreme example, there are several important lessons that follow from this story.

Firstly, business can't always wait for software systems to be redeveloped, and can often show high levels of ingenuity in bypassing the constraints imposed by an unimaginative design.

Secondly, the users were able to take advantage of a Notes field that had been deliberately underdetermined to allow for future expansion.

Furthermore, users may find clever ways of using and extending a system that were not considered by the original designers of the system. So there is a divergence between technology-as-designed and technology-in-use.

Now let's think what happens when the IT people finally get around to replacing the old billing system. They will want to migrate customer data into the new system. But if they simply follow the official documentation of the legacy system (schema etc), there will lots of data quality problems.

And by documentation, I don't just mean human-generated material but also schemas automatically extracted from program code and data stores. Just because a field is called CUSTADDR doesn't mean we can guess what it actually contains.

Here's another example of an underdetermined data element, which I presented at a DAMA conference in 2008. SOA Brings New Opportunities to Data Management.

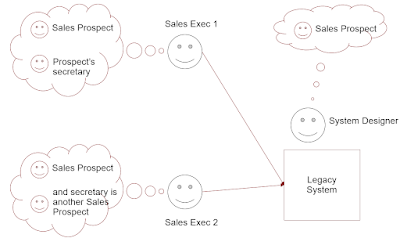

In this example, we have a sales system containing a Business Type called SALES PROSPECT. But the content of the sales system depends on the way it is used - the way SALES PROSPECT is interpreted by different sales teams.

- Sales Executive 1 records only the primary decision-maker in the prospective organization. The decision-maker’s assistant is recorded as extra information in the NOTES field.

- Sales Executive 2 records the assistant as a separate instance of SALES PROSPECT. There is a cross-reference between the assistant and the boss

Now both Sales Executives can use the system perfectly well - in isolation. But we get interoperability problems under various conditions.

- When we want to compare data between executives

- When we want to reuse the data for other purposes

- When we want to migrate to new sales system

(And problems like these can occur with packaged software and software as a service just as easily as with bespoke software.)

So how did this mess happen? Obviously the original designer / implementer never thought about assistants, or never had the time to implement or document them properly. Is that so unusual?

And this again shows the persistent ingenuity of users - finding ways to enrich the data - to get the system to do more than the original designers had anticipated.

And there are various other complications. Sometimes not all the data in a system was created there, some of it was brought in from an even earlier system with a significantly different schema. And sometimes there are major data quality issues, perhaps linked to a post before processing paradigm.

Both data migration and data integration are plagued by such issues. Since the data content diverges from the designed schemas, it means you can't rely on the schemas of the source data but you have to inspect the actual data content. Or undertake a massive data reconstruction exercise, often misleadingly labelled "data cleansing".

There are several tools nowadays that can automatically populate your data dictionary or data catalogue from the physical schemas in your data store. This can be really useful, provided you understand the limitations of what this is telling you. So there a few important questions to ask before you should trust the physical schema as providing a complete and accurate picture of the actual contents of your legacy data store.

- Was all the data created here, or was some of it mapped or translated from elsewhere?

- Is the business using the system in ways that were not anticipated by the original designers of the system?

- What does the business do when something is more complex than the system was designed for, or when it needs to capture additional parties or other details?

- Are classification types and categories used consistently across the business? For example, if some records are marked as "external partner" does this always mean the same thing?

- Do all stakeholders have the same view on data quality - what "good data" looks like?

- And more generally, is there (and has there been through the history of the system) a consistent understanding across the business as to what the data elements mean and how to use them?

Related posts: Post Before Processing (November 2008), Ecosystem SOA 2 (June 2010), Technology in Use (March 2023)