|

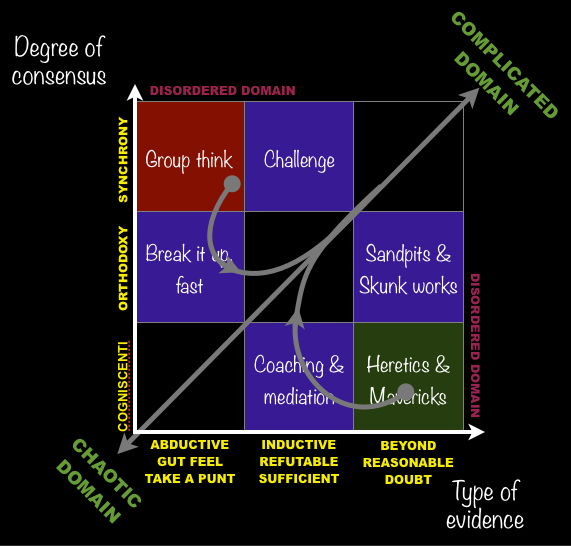

| Source: Dave Snowden, Cognitive Edge April 2013 Used with permission |

At present, I believe there are two main clusters of Enterprise Architecture practice:

Mainstream EA. This is where TOGAF and Zachman and all the other popular frameworks sit. These frameworks are largely based on a 1980s view of enterprise and IT, contain apparently inflexible classification schemes, and are strongly aligned to the commercial interests of the large software companies and system integrators (IBM, Cap-Gemini, and the rest). These frameworks sit in the top left corner of Snowden's chart, with a high level of consensus and a very weak evidence-base.

If we look at Mainstream EA in terms of Boisot's I-Space, I would suggest these frameworks appear as premature codifications of ungrounded abstractions. The attempted diffusion of these codified abstractions is then ineffectual, because these ungrounded categories lack any relevance to real business challenges. From time to time, practitioners may well be able to do some useful work, and they may even be persuaded that their success is a consequence of using these frameworks. But it is also possible that these occasional successes are despite the framework and not because of it.

Next Practice EA, with a smaller but growing number of practitioners and researchers proposing radical alternatives to Mainstream EA. This community includes some well-placed industry analysts (such as Nick Gall of Gartner) as well as a significant number of independent consultants. Many of these alternatives involve hybrids of EA with some other discipline, such as Systems Thinking or Design Thinking. However, the evidence base for these hybrids is if anything even weaker than for Mainstream EA frameworks, and there is no consensus whatsoever. Few if any of these hybrids have been tested in full, and sometimes they appear to consist of little more than a bricolage of ill-assorted concepts and techniques, which I call Methodological Syncretism.

What would it take for Next Practice EA to develop either sufficient evidence or sufficient consensus to represent a serious challenge to Mainstream EA? It seems to me that the answer lies at the Concrete, Undiffused, Uncodified corner of the I-Space cube. What I have found highly frustrating in many discussions with both enterprise architects and systems thinkers is an apparent belief in the absolute virtues of abstraction. So instead of discussing concrete business problems, we find ourselves discussing generic categories of business problem. Many of the discussants either don't appreciate the difference between "Cost Saving" and "Cost Saving at Smartchester College", or they think that discussing the general category is more intellectually respectable than discussing a specific case.

There is of course a reason why discussing specific cases is treated with disdain in some quarters, which has to do with the way cases are used in some business schools, notably Harvard Business School. There are two ways to explore a specific case. In the Harvard approach, as I understand it, students are presented with cases which they need to "solve", using a light sprinkling of theoretical concepts. You use the theory if it works; if it doesn't, you ignore it. This approach isn't designed to produce a deeper understanding either of the cases or the underlying theory. The alternative (which I prefer) is a much more reflective and reflexive approach, where you use the case as an instrument to understand and test and refine the underlying theory. The aim is to end up with a rich and specific narrative that is both empirically and theoretically grounded. Only when we have a sufficient number of these narratives do we begin, with great caution, to generalize from them. But that's a lot harder and more time-consuming than putting together a blog or presentation full of post-modern cleverness. (Okay, I can be as guilty of this as anyone else.)

This is an extract from my draft eBook Towards Next Practice Enterprise Architecture, available from LeanPub.

These and related issues were discussed at a public meeting Perspectives on Enterprise Architecture and Systems Thinking, in Central London, June 14th 2013. For my own presentation slides, subsequent notes and links to reports by other participants, see Schism and Doubt (July 2013).